Boundaries: Asserting Yourself, Respecting Others

This article has been languishing on my "to do" list for almost eighteen months, following my completion of an applied psychology degree with my final (and best) subject on relationship dynamics. It also follows from witnessing many conversations on various social media forums illustrating a great deal of confusion across many vectors around the subject of personal boundaries. It may even include a bit of knowledge gleaned from my own experiences. In any case, it basically consists of five major propositions.

This article has been languishing on my "to do" list for almost eighteen months, following my completion of an applied psychology degree with my final (and best) subject on relationship dynamics. It also follows from witnessing many conversations on various social media forums illustrating a great deal of confusion across many vectors around the subject of personal boundaries. It may even include a bit of knowledge gleaned from my own experiences. In any case, it basically consists of five major propositions.

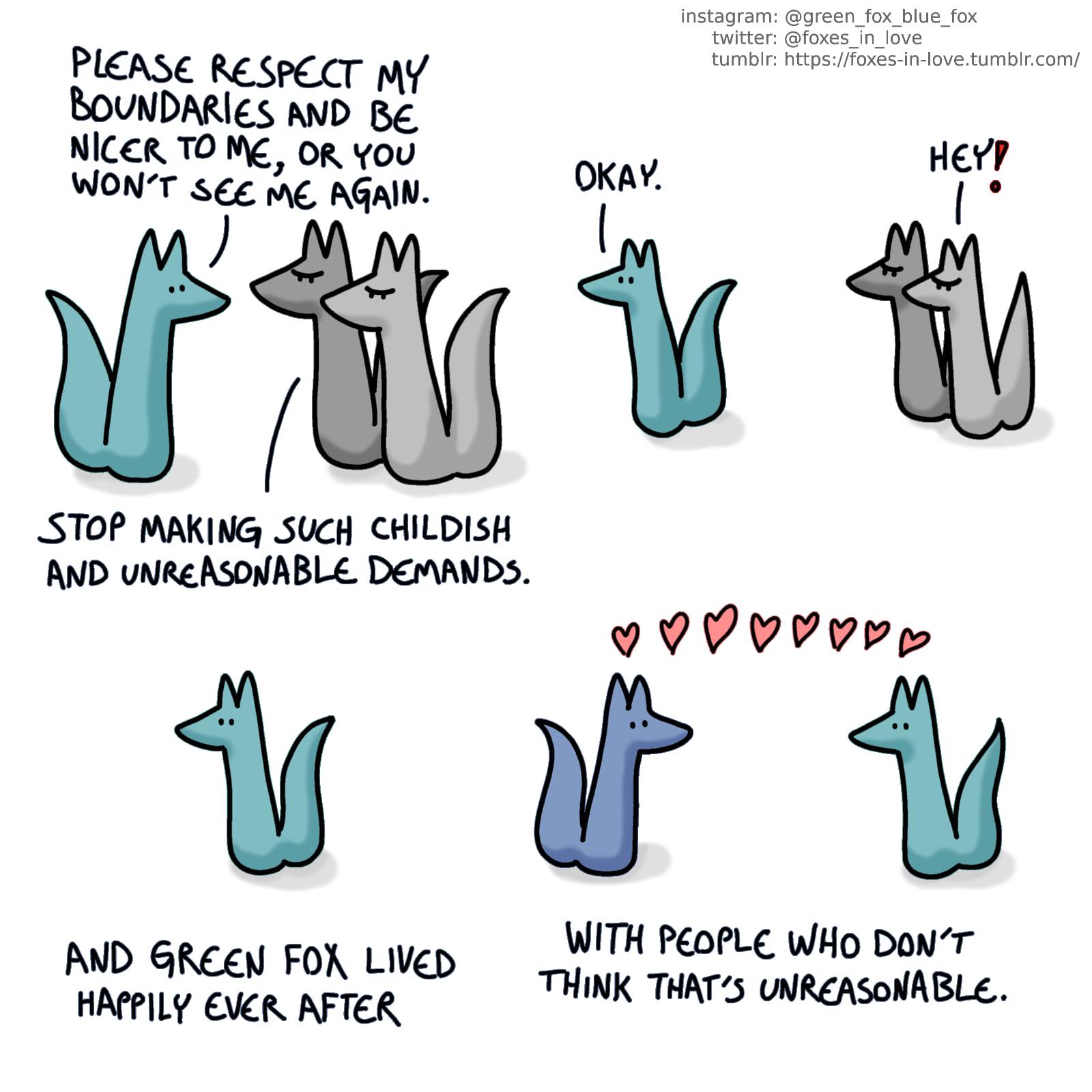

1) Personal boundaries are your responses; they are not demands imposed on other people.

2) Be consistent with your personal boundaries. Empathy without boundaries is self-harm.

3) Your personal boundaries give respect and autonomy to others and provide early warnings of potential incompatibilities.

4) Your boundaries should be open to reconsideration and revision.

5) Your boundaries are compatible with unconditional love.

Proposition 1) Personal boundaries are your responses; they are not demands imposed on other people.

The first, and most significant, confusion is that people don't quite understand what a personal boundary is. Many people think it's an iron-clad rule of behavioural expectations that one can impose on other people's behaviour. This confusion is understandable given the name, suggesting a border between the self and others. However, it is about the boundaries within yourself of your values and comfort level, what you consider to be acceptable or unacceptable behaviour ("in-bound", "out-of-bounds"), and your responses. One doesn't set boundaries on other people, one sets them within oneself.

The clearest contrast is usually given between boundaries and demands and requests. With a demand, one is trying to make another person change their behaviour so it better matches what the requester wants to see from them. Care is required that such requests and demands respect the person's autonomy. However, one can express a request, and if that is ignored then your boundary is what you do about. Boundaries are not demands on another person, not matter how justified the demand is. They are a reflection of your internal values they should be expressed in expressed and implemented in the general sense of behaviour rather than specific individuals.

"I don't want you to raise your voice at me", is a demand and is directed at a specific person.

"I will walk away if someone raises their voice at me", is a boundary that is directed at nobody in particular and it's what you will do in a situation that is contrary to your values or comfort.

"Please do not call me", is a request and is directed at a specific person.

"If anyone calls me when I've asked them not to, I will block their number", is a boundary. It is your action, and it is expressed in a general case and not to a person.

Demands and ultimatums for that matter are not necessarily "bad", especially when there is an egregious breach of interpersonal space. It is very much a demand to say "Stop hitting me!". It is, however, a boundary when you decide what you will do about a person who is violent toward you ("leave and never return, because it will set a new standard if you stay and it will get worse", is pretty sound advice at this point).

Proposition 2) Be consistent with your personal boundaries. Empathy without boundaries is self-harm.

This leads to the second hurdle that many people face; they are not consistent with their boundaries. Again, this is quite understandable. We tend to care a lot more, in concrete terms, about a loved one than we do about a distant stranger in another country, even if we have an abstract principle of universality that all people deserve equal rights and treatment. But a differentiated application of boundaries is a very quick path to ending up in an abusive relationship; whether it is with a friend, romantic interest, co-worker, or family member. The moment that our responses to behaviour that breaches our boundaries varies is the moment that we undermine our own values and sense of self, providing the opportunity for people that we have excused to walk all over us.

Consider the previous example of a person who is subject to violence from some source. They might, quite reasonably, have various boundaries in accord with their values about what they would do if subject to violence. But how often, as domestic violence support workers know all too viscerally, that people make excuses for a loved one who engages in violence? This is a particularly blunt example because there is so much evidence that if one stays in a relationship where a partner has been violent it will set a new bar of acceptable behaviour, and will eventually escalate until someone ends up in hospital, or worse. Excuses such as "He only does it when he's drunk", or "She really does love me deep down" become dangerous excuses. Whilst it is true that violent abusers often have deep-seated issues that they are struggling with, one's empathy toward a loved one, or attempt to understand them, must never become an excuse. Empathy without boundaries is self-harm.

(It absolutely must be mentioned that there are many other legitimate reasons why a person stays with a violent partner. They may lack the independent finances to leave, they may be a member of a community that will turn against them and blame the victim, they may worry about what will happen to their children, etc. This example is only relevant to where one accepts abusive behaviour because of emotional or familial closeness.)

A recent conversation involved the frustration that a person felt because their partner would cheat on them and do drugs behind their back. Their partner's response was "I don't tell you that I do these things because I don't like how you react and how that makes me feel". The person obviously cared about their partner person a great deal, but they hadn't established boundaries for themselves that asserted their values. As a result, there was dissonance between the love they had for their partner and their own sense of mental comfort. Here's an example of how such a conversation should go:

You: "I will not be in a relationship with someone who cheats on me, does drugs, and lies to me about it"

Them: **Carries out activities mentioned.**

You: "OK, bye"

Proposition 3) Your personal boundaries give respect and autonomy to others and provide early warnings of potential incompatibilities.

This leads to the third consideration; having personal boundaries respects the autonomy of others as well, within the general distinction between self-regarding and other-regarding acts. It is also recognises that people can have their own reasons for their responses, and they are under no obligation to disclose them. It doesn't matter if another person understands them, or even accepts them if explained. And the same applies for them as well! You have no right to have their boundaries explained to you, and you have no right to determine what another person's boundaries are. They're their boundaries, not yours, just as your boundaires are yours, not theirs. Nobody, except for the person who is setting their own boundaries, needs to agree with them for the boundary to be valid. It is on that basis that two people with a strong sense of personal boundaries can both respect each other's decisions and discover potential incompatibilities early.

Person A: "You need to be on time". (This is a demand)

Person A: "If anyone is more than 20 minutes late, I will not wait for them." (This a boundary)

Person B: "We're in a relationship. You should wait for me". (This is a demand)

Person B: "I will not be in a relationship with someone who doesn't wait for me" (This is a boundary)

Who is right here? Some people, who are sticklers for time, might think Person A is. Others, who believe that a partner should always be there for them, might think Person B is. According to personal boundaries, however they are both right! Expressed as boundaries, rather than demands, both Person A and Person B, is making a conscious choice about what they think is in-bound or out-of-bound behaviour. Many people might also think "This is not something worth breaking up over!", and such people are right as well. Lateness might be an acceptable in-bound behaviour for some people, and it might be considered intolerable for others. The reality is that people have different priorities in their life. There is no point Person A saying "If you respected me you would be on time", because Person B can just as easily respond "If you respected me, you would wait for me". It is simply a matter that Person A and Person B seem to have a fundamental incompatibility.

Proposition 4) Your boundaries should be open to reconsideration and revision.

This leads to the fourth point; personal boundaries should not be permanent walls of steel. Everyone should take the opportunity to reconsider their own values and what is an acceptable comfort level for themselves. It is through such revision are we capable of improvement and growth as a person. Also, circumstances change as well. Further, and perhaps most importantly, we need to have the capability to admit that we have erred in our judgment.

Let's give an example of a person who has a good income, and they lend readily to family and friends. Although not clearly stated as such consciously, they have a generous and helpful boundary of behaviour when it comes to lending money and they are comfortable with that. But circumstances have changed; perhaps their income has suddenly dropped due to unemployment, or maybe they have just become weary of people borrowing money of them. They could change what is acceptable "in-bound" behaviour to them to what is comfortable according to their own criteria (e.g., "I will not lend any more money to people who already owe me money").

Consider Person B in Proposition 3, who decides that they can't be in a relationship with someone who doesn't wait for them. After some consideration and perhaps discussion with close friends, they come to realise that their timing is tawdry and needs to improve. That it is understandable that another person doesn't want half an hour or more in the rain for them to turn up etc. Maybe breaking up with someone when you were late is a bit harsh on them. So their boundary is reconsidered; not only do they make more of an attempt to turn up on time, they are more accepting when a person decides to do something else when they are late. The important thing for a sense of self however, is that they are changing their boundary because their values have evolved, rather than changing their boundary for the sake of someone else (see Proposition 2).

Proposition 5) Your boundaries are compatible with unconditional love.

Unconditional love is a selfless act, whereby one offers love freely and altruistically. However, it is a common mistake to assume that unconditional love encourages co-dependency and enables abusive behaviour. This can be the case where a person doesn't have boundaries; that they are unconditionally giving to another person, unconditionally forgiving a person's transgressions, and so forth. That would certainly not be healthy!

The two words should not be seen separately, but rather as a single phrase. It is the love that is unconditional; one can still offer love freely whilst having many firm personal boundaries. Offering love and forgiveness and does not mean accepting harmful actions or discomfort.It is not contradictory to say: "When a person talks over me, I'll leave the conversation. You have just done that, so I'm hanging up. I still love you".

Ultimately it would be quite astounding if people could develop a greater sense of love for all with firm but evolving personal boundaries that respect others whilst asserting the self with a security. There are many reasons beyond the scope of this short essay on why this is not the case, but at the very least it is hoped that this will provide at least some good for people who have strained and confused relationships with friends, family, and romantic partners.

- lev.lafayette's blog

- Log in to post comments

Comments

lev.lafayette

Wed, 2025-02-05 12:33

Permalink

Elaborations

I received some correspondence from a reader which warrants elaboration on two issues that they raised.

The first is the distinction between demands and requests. As has been well-established, demands are have a command-orientation and should be used sparingly but also can reflect an immediate need for compliance ("stop hitting me", "stop shouting at me"). A request comes with the possibility of negotiation ("could you take the rubbish out, please?").

The second was the difference between being consistent with boundaries and having boundaries open to revision. Consistency is the external application, that is, because they are your boundaries they should applied regardless of the other party. Revision is the internal application, the recognition that our own opinions may not be entirely and eternally true. There is no contradiction between being consistent with a boundary toward others, and being open to having a boundary revised.